Fundamental Design and Operational Dissonance

The core question of whether Bottom Discharge Valves can handle both dry bulk and liquids strikes at the heart of valve engineering. The short, practical answer is that they are primarily and optimally designed for dry bulk solids, and their application for true liquids is highly limited and often inadvisable. The reason lies in the fundamental difference in material behavior. Dry bulk materials (powders, granules, pellets) have internal friction and can form stable arches. Bottom Discharge Valves are designed to break this bridging and allow gravity-driven, controlled flow of these particulate systems. Liquids, in contrast, are incompressible fluids that exert hydrostatic pressure and seek the path of least resistance instantly.

A standard knife-gate or clamshell Bottom Discharge Valve for dry bulk relies on a mechanical seal that contacts the material to shut off flow. This seal is effective against solid particles but is not designed to contain the pervasive pressure of a liquid, which will find and exploit any microscopic leak path. Using a dry bulk valve for liquids almost guarantees leakage. Furthermore, the actuation force required to cut through a settled dry solid is different from the force needed to seal against fluid pressure, potentially leading to valve failure.

Critical Design Features for Dry Bulk vs. Liquid Service

The valve's construction reveals its intended purpose. For dry bulk handling, specific features are non-negotiable. The valve body is often designed to be as short as possible to prevent material hang-up. Seals are made from abrasion-resistant materials like urethane, and the sealing surface may be angled or contoured to shear through material. There is no expectation of a pressure-tight seal in the same way a liquid valve requires.

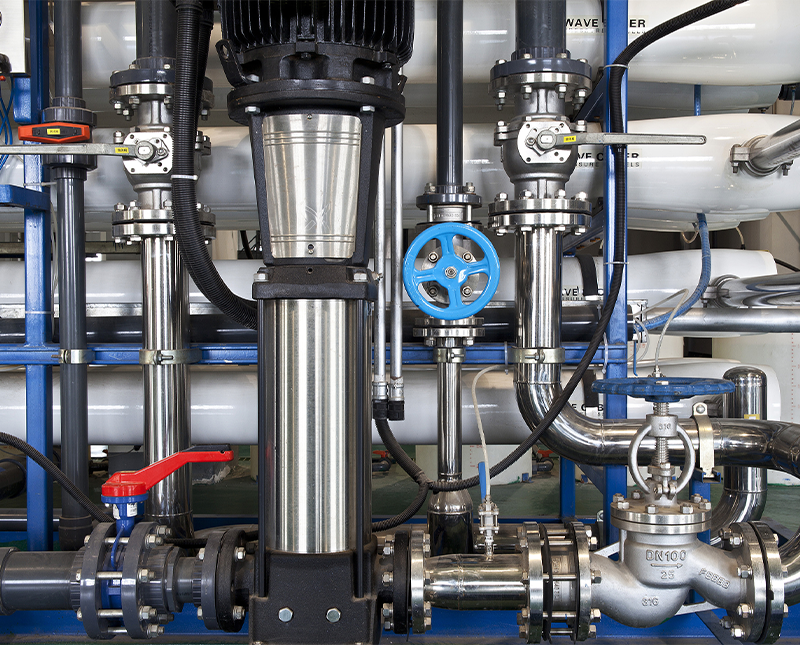

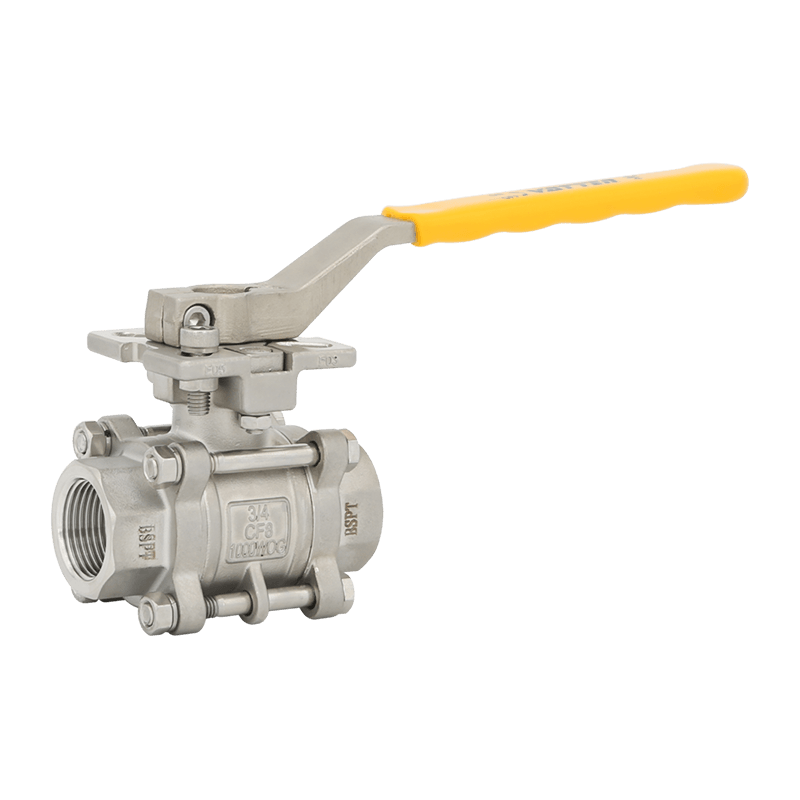

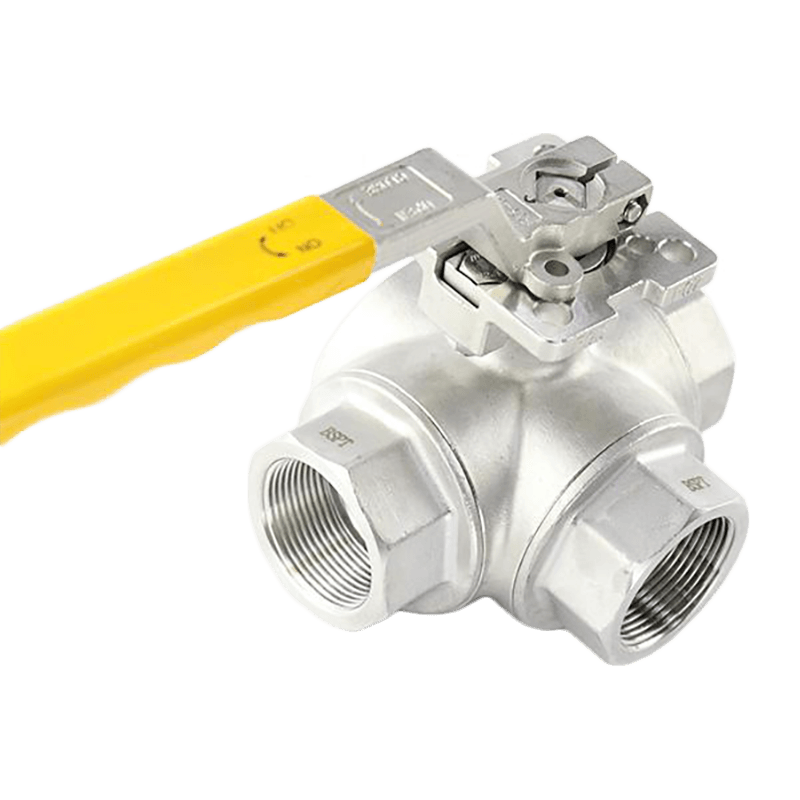

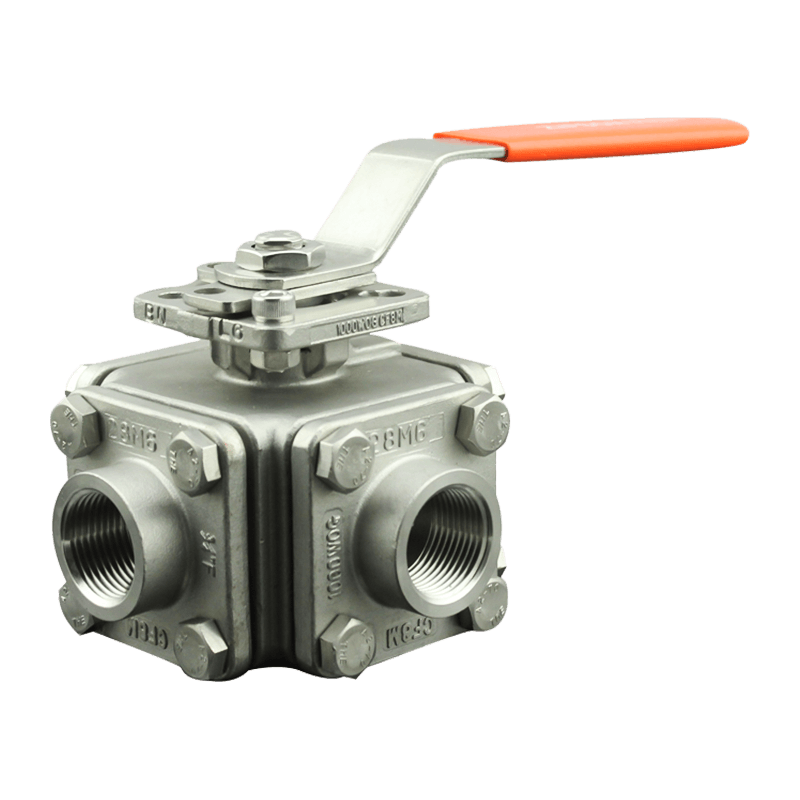

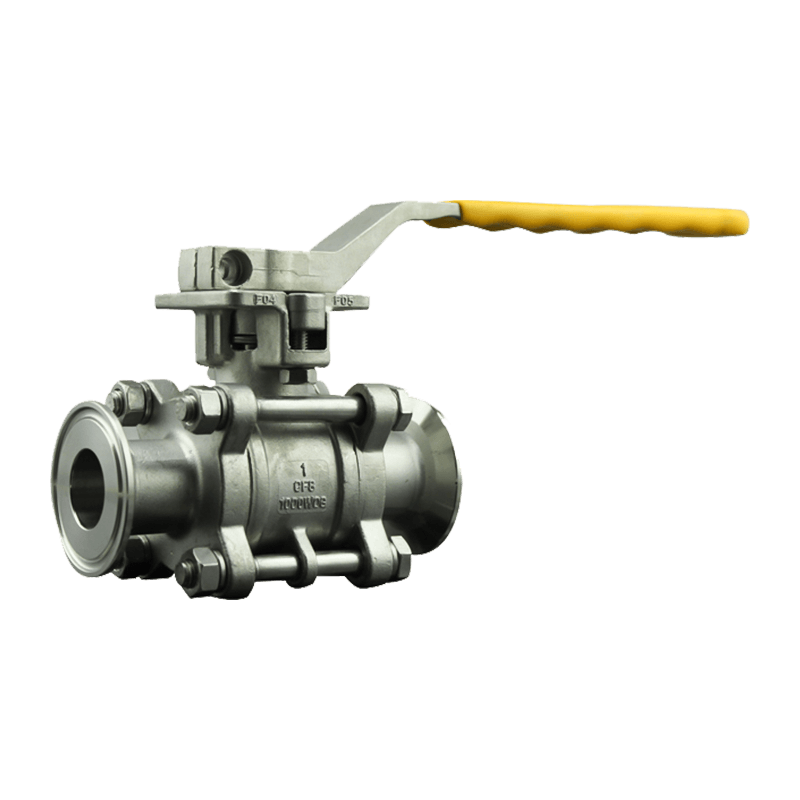

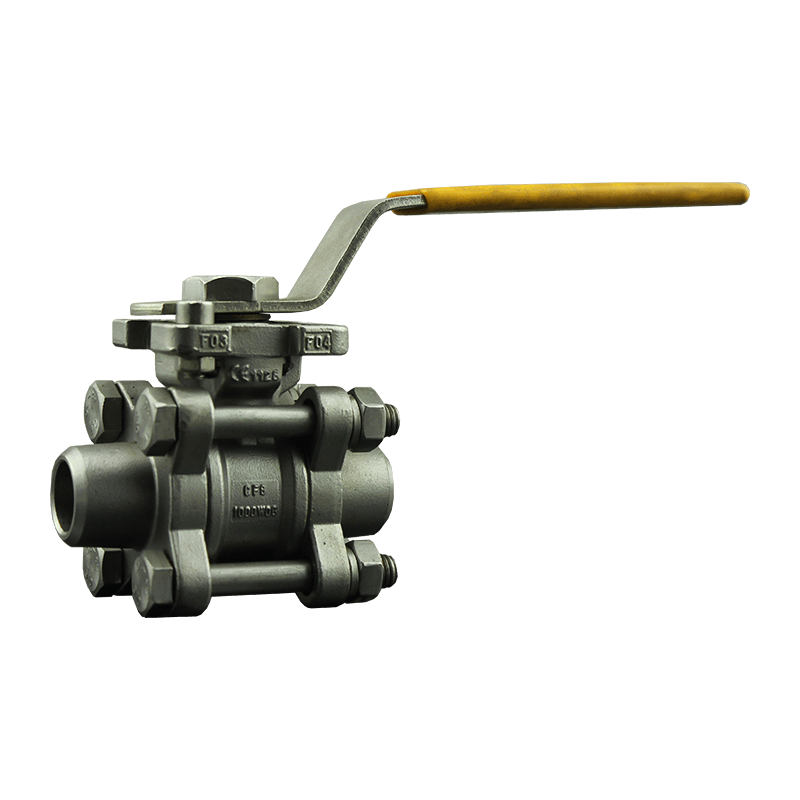

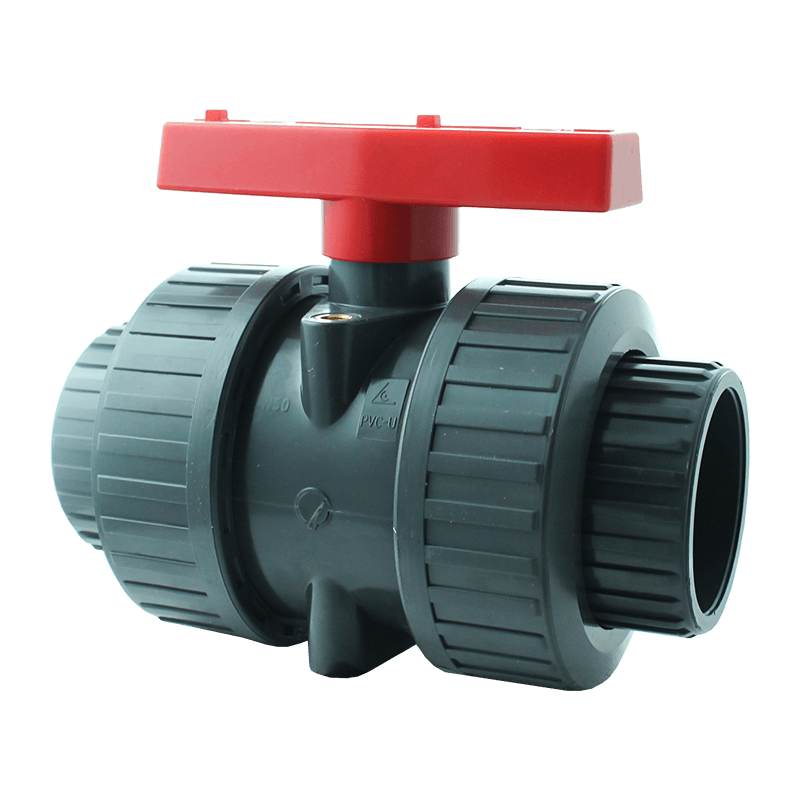

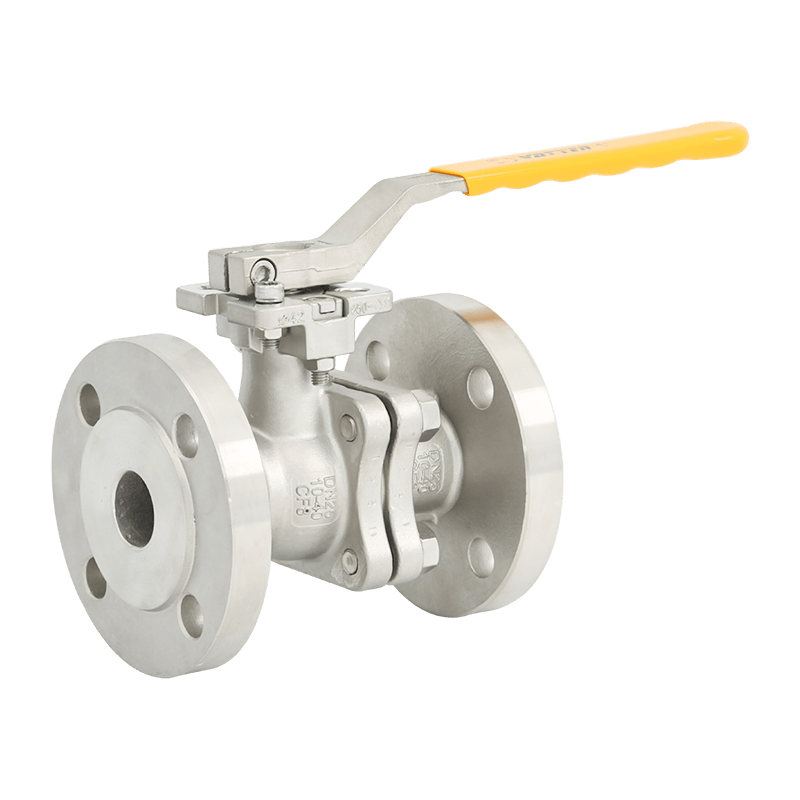

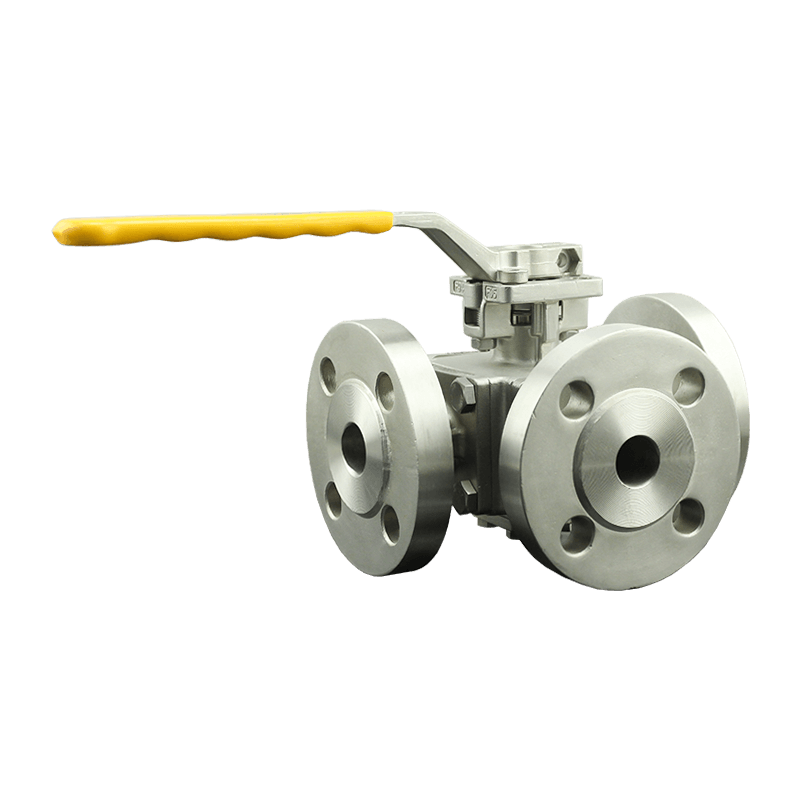

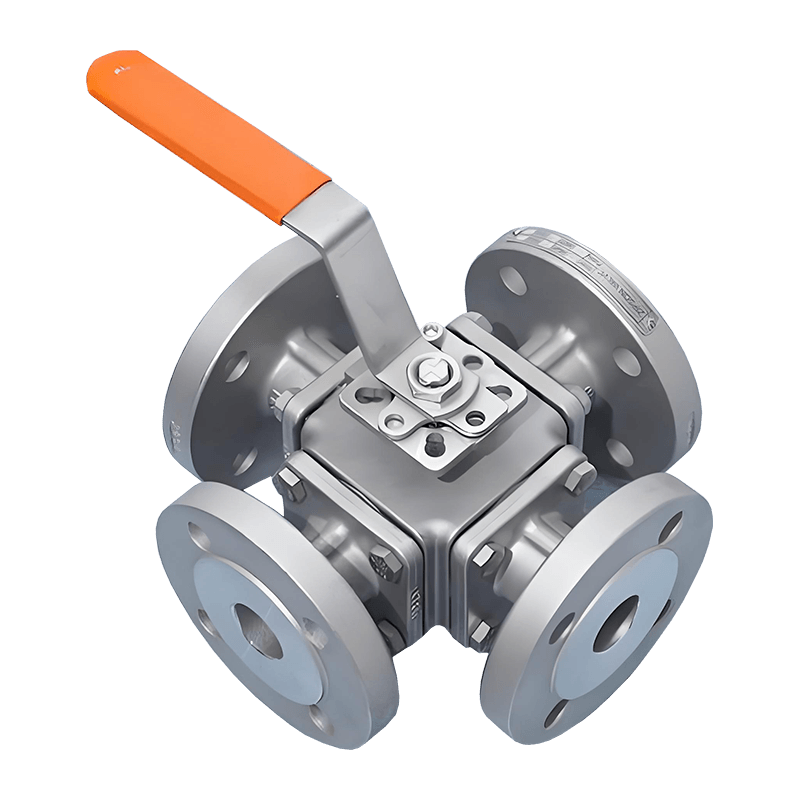

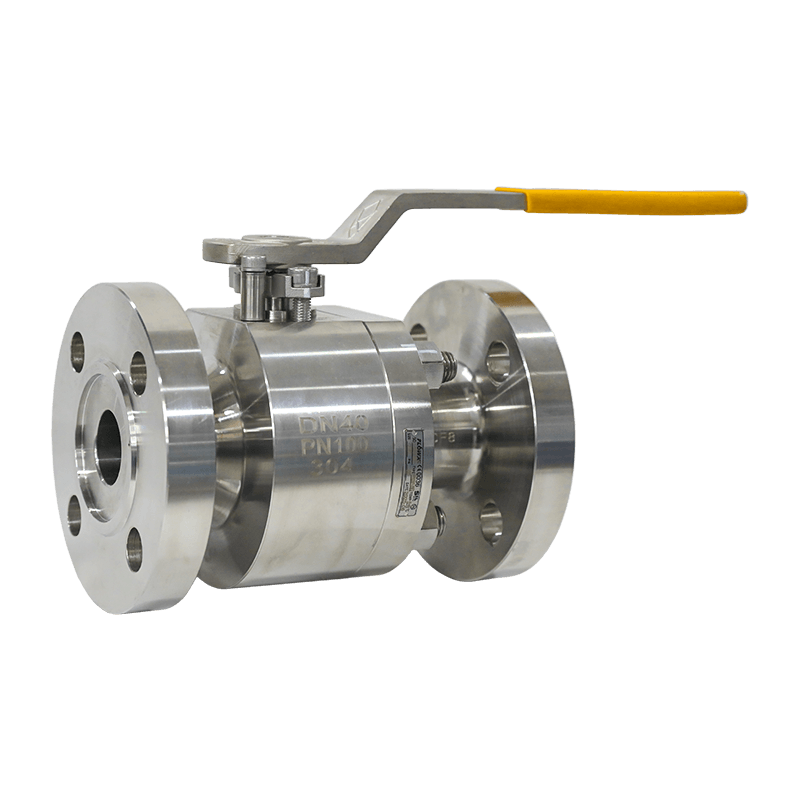

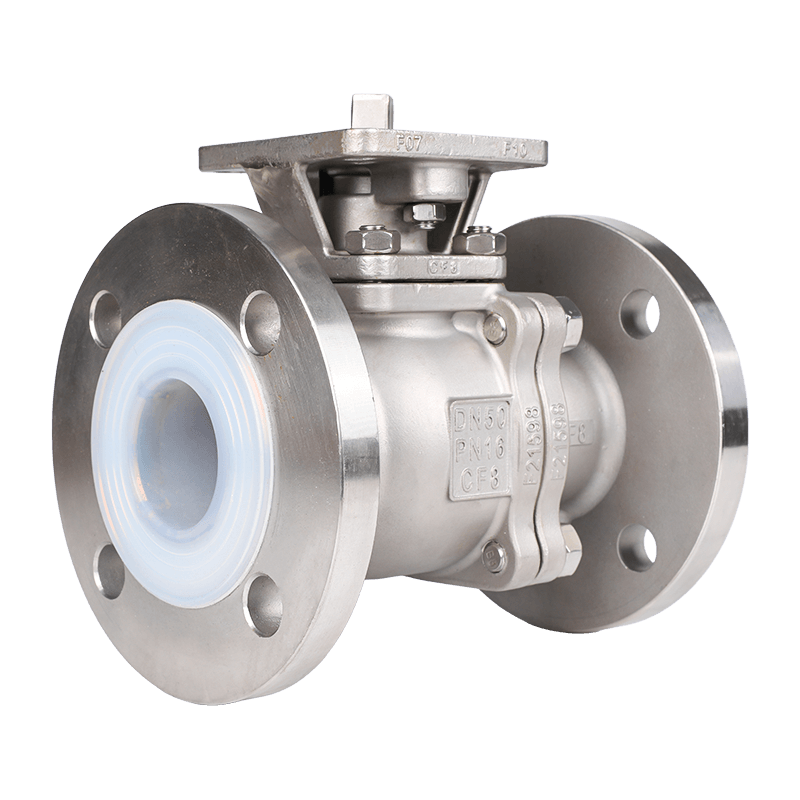

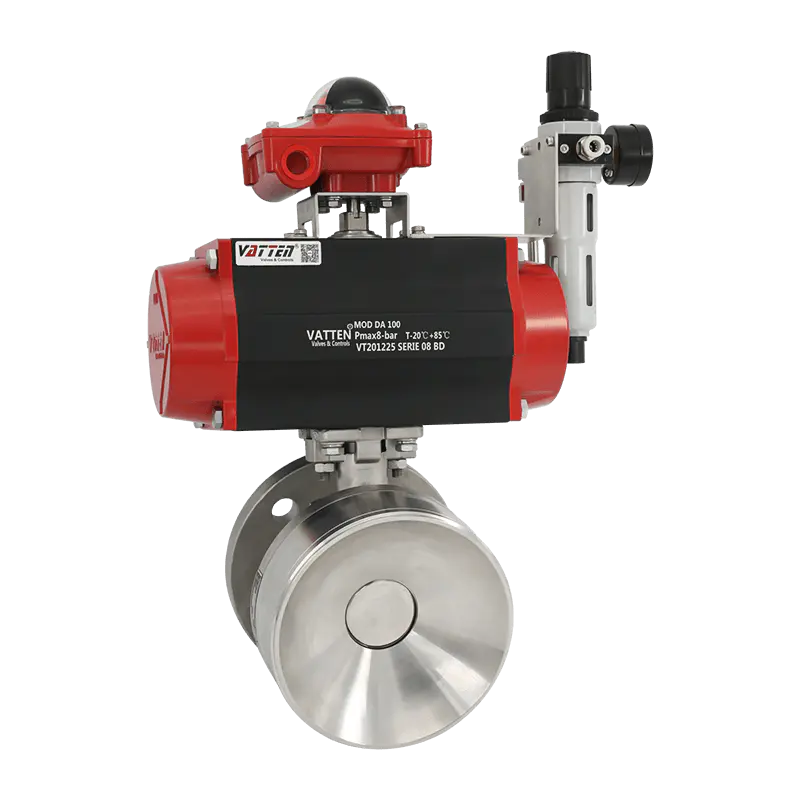

For liquid service, valves are pressure-rated, have completely sealed bonnets or stems, and use elastomeric seals (like O-rings or gaskets) that deform to create a perfect, continuous barrier. Butterfly valves, ball valves, or plug valves are standard. The table below contrasts the design priorities:

| Design Aspect | Bottom Discharge Valve (Dry Bulk Focus) | Standard Liquid Valve (e.g., Ball Valve) |

| Primary Function | Prevent bridging, ensure mass flow, shut off solid stream | Contain pressure, provide bubble-tight shut-off |

| Seal Type | Knife-edge, clamshell, or slide-gate; abrasion-resistant | Elastomeric (EPDM, Viton), machined metal-to-metal |

| Body Design | Short, often with steep walls to promote flow | Compact, pressure-rated chamber |

| Key Concern | Abrasion, material degradation, flow aid | Corrosion, pressure integrity, cavitation |

The Gray Area: Slurries and High-Moisture Materials

A practical, borderline application exists for materials that behave neither as a perfect dry solid nor a free-flowing liquid. This is the realm of slurries, sludges, and moist bulk materials. In these cases, a specialized Bottom Discharge Valve can be applicable, but only with significant modifications.

Required Modifications for Semi-Solid Applications

To handle viscous or semi-solid materials, the valve design must evolve. A standard knife-gate may struggle. Instead, a specialized pinch valve or a heavy-duty, fully lined knife-gate valve with enhanced sealing is used. The critical modifications include:

- Full Bore and Body Liners: The valve interior is lined with a flexible, corrosion-resistant material (like rubber or PTFE) that can contain the paste or slurry and provide a better seal when closed.

- High-Pressure Actuators: Increased actuation force is needed to shear through and seal the often-sticky material.

- Flush Ports: Integrated cleaning ports to prevent material from solidifying or packing in the valve body and seal areas.

- Special Seal Designs: Using inflatable seals or dual seals that can accommodate and compress the varying material consistency.

Even with these changes, the valve is not handling a pure liquid but a non-Newtonian fluid or damp solid. Its selection requires careful analysis of material viscosity, particle size, and abrasiveness.

Practical Selection Guidelines and Recommendations

Making the correct choice is crucial for system safety, efficiency, and cost. Use this constructive guideline to determine suitability.

- For Dry Bulk Solids (Free-Flowing to Cohesive): Bottom Discharge Valves are the default and optimal choice. Select knife-gate, double-flap, or sector valves based on material characteristics.

- For Slurries & Pastes (50-85% Solids): A specialized, fully lined Bottom Discharge Valve or a pinch valve is a viable and common solution. Consult the valve manufacturer with exact material samples and data sheets.

- For True Liquids (Water, Oil, Chemicals): Avoid standard Bottom Discharge Valves. Select a purpose-built liquid valve (ball, butterfly, diaphragm, or globe valve) with the appropriate pressure rating and seal material.

A final, critical consideration is cleaning and cross-contamination. In facilities that process both dry and wet batches, using the same valve is a major contamination risk. Residual liquid in a valve designed for dry product can cause clumping, spoilage, or chemical reactions. Conversely, dry material residue can contaminate a liquid stream. Dedicated valves for each service are the only reliable solution for multi-product plants.

Conclusion: A Question of Physics, Not Just Hardware

Ultimately, the use of Bottom Discharge Valves is dictated by material science. Their design physics are tailored to overcome the specific challenges of particulate solids—bridging, ratholing, and abrasive wear. While engineered adaptations can push their application into the realm of thick slurries, they fundamentally lack the inherent pressure-containing design required for efficient, leak-free handling of free-flowing liquids. Specifying the correct valve is not a matter of finding a multi-purpose tool, but of applying the precise tool engineered for the specific phase and behavior of your material.

English

English Deutsch

Deutsch Indonesia

Indonesia